The Mountain Experience

WHERE IS KILIMANJARO?

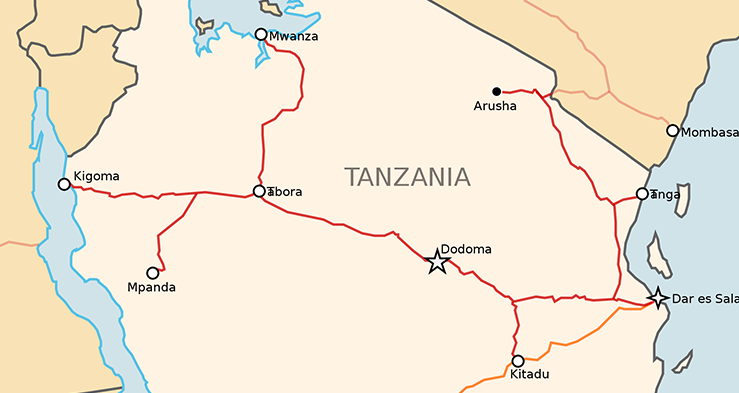

Kilimanjaro sits on the northern border of Tanzania. Overlooking Kenya, it’s just over 200 miles south of the Equator. You may be surprised to learn that the area is not particularly mountainous; indeed, the nearest mountain to Kilimanjaro is Mount Meru, over 60 km southwest.

WHY IS IT CALLED ‘KILIMANJARO’?

Despite extensive studies into the etymology of the name Kilimanjaro, nobody is completely sure where it comes from or what exactly it means. When looking for the name’s origin, as we see it – there are 3 main possibilities.

- It seems only sensible to begin such a search in one of the local Tanzanian dialects. More specifically, it makes sense to start with the language spoken by those who live in its shadow, namely the Chagga people. The name Kilimanjaro bears no resemblance to any word in the Chagga vocabulary, but if we divide the name into two parts, then a few possibilities present themselves.One possibility is that Kilima is derived from the Chagga term kilelema, meaning ‘difficult or impossible’, while jaro could come from the Chagga terms njaare (‘bird’) or jyaro (‘caravan’). In other words, the name Kilimanjaro could mean something like ‘That which is impossible for the bird’, or ‘That which defeats the caravan’ – names which, if this interpretation is correct, are clear references to the sheer enormity of the mountain.There’s also an early spelling of Kilimanjaro, from the title of a beautiful biography by French missionary, Mgr LeRoy.Whilst this is perhaps the most likely translation, it is not, in itself, particularly convincing, especially when one considers that while the Chagga language would seem the most logical source for the name. The Chagga people themselves do not actually have a name for the mountain! They don’t see Kilimanjaro as a single entity but as two distinct, separate peaks, namely Mawenzi and Kibo. (These two names, incidentally, are definitely Chagga in origin, coming from the Chagga terms kimawenzi – ‘having a broken top or summit’ – and kipoo – ‘snow’ – respectively.)

- Assuming Kilimanjaro isn’t Chagga in origin, the most likely source for the name Kilimanjaro may be Swahili, the main language for most Tanzanians. Johannes Rebmann’s good friend and fellow missionary, Johann Ludwig Krapf, wrote that Kilimanjaro could either be a Swahili word meaning ‘Mountain of Greatness’ – though he is noticeably silent when it comes to explaining how he arrived at such a translation – or a composite Swahili/Chagga name meaning ‘Mountain of Caravans’; jaro, as we have previously explained, being the Chagga term for ‘caravans’.Thus the name could be a reference to the many trading caravans that would stop at the mountain for water. The major flaw with both these theories, however, is that the Swahili term for mountain is not kilima but mlima – kilima is actually the Swahili word for ‘hill’!

- The third and least likely dialect of origin: Masai, the major tribe across the border in Kenya. But while the Maasai word for spring or water is njore, which could conceivably have been corrupted down the centuries to njaro, there is no relevant Masai word similar to kilima. Furthermore, the Masai call the mountain Oldoinyo Oibor, which means ‘White Mountain’, with Kibo known as the ‘House of God’, as Hemingway has already told us at the beginning of his – and our – book. Few experts, therefore, believe the name is Masai in origin.

Other theories include the possibility that njaro means ‘whiteness’, referring to the snow cap that Kilimanjaro permanently wears, or that Njaro is the name of the evil spirit who lives on the mountain, causing discomfort and even death to all those who climb it. Certainly the folklore of the Chagga people is rich in tales of evil spirits who dwell on the higher reaches of the mountain, and Rebmann himself refers to ‘Njaro, the guardian spirit of the mountain’; however, it must also be noted that the Chagga legends make no mention of any spirit going by that name. And so, we are none the wiser. In a sense though, this is what is truly important: What the mountain means to the 50,000 people who walk up it every year. That is far more meaningful than any name we ascribe to it. Speaking of trekking, let’s talk more about the trek itself and its level of safety.

IS CLIMBING KILIMANJARO SAFE?

Kilimanjaro isn’t technically challenging, but at 19,341 ft (5,895 m), the altitude for many folks is.

Almost every climber will experience some of the effects of altitude. It’s important to know what to expect and how best to prepare yourself. (Towards the end of this guide, you will discover more about Altitude Sickness and how to treat it – How to prep beforehand and how to handle during the trek itself.)

WHEN IS THE BEST TIME TO CLIMB KILIMANJARO?

Due to Mount Kilimanjaro’s proximity to the equator, this region does not experience the extremes of winter and summer weather, but rather dry and wet seasons. It is possible to climb Kilimanjaro year round, however, it is best to climb when there is a lower possibility of precipitation. The dry seasons are from the beginning of December through the beginning of March, and then from late June through the end of October. These are considered to be the best times to climb in terms of weather, and correspondingly are the busiest months (high season). Our group climbs are scheduled to correspond with the dry season.

The primary issue for choosing a season is safety, as the risks associated with climbing increase significantly when the weather is foul. The effects of rain, mud, snow, ice and cold can be very strenuous on the body. Correspondingly, your chances of a successful summit also increase significantly with nice weather. Of course, the mountain gets more foot traffic during these periods as well.

The table below lists the relative temperature, precipitation, cloudiness and crowds during the calendar months.

| Month | Temperature | Precipitation | Cloudiness | Crowds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | Warm | Medium | Low | High |

| February | Warm | Medium | Low | High |

| March | Moderate | High | Medium | Low |

| April | Moderate | High | High | Low |

| May | Moderate | High | High | Low |

| June | Cold | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| July | Cold | Medium | Low | High |

| August | Cold | Low | Low | High |

| September | Moderate | Low | Low | High |

| October | Moderate | Low | Medium | Medium |

| November | Moderate | High | Medium | Low |

| December | Moderate | Medium | Medium | Medium |

From January through mid-March are the warmest months, with clear skies in the mornings and evenings. During the day, clouds may appear along with brief showers. The long, rainy season spans from the end of March to early June. We do not recommend climbing during this time unless you are an experienced backpacker who has trekked in similar conditions. It can be very wet and visibility may be low due to heavy clouds. The crowds are gone though.

From mid-June to the end of October, the mountain is generally a bit colder, but also drier. The short rainy season spans from the beginning of November to the beginning of December. Afternoon rains are common, but skies are clear in mornings and evenings.

Note that the rains are unpredictable and may come early or extend beyond their typical time frames. It is possible to experience mostly dry weather conditions during the rainy season, just as it is possible to have heavy rain during the

dry season.

HOW TO SUMMIT AT THE FULL MOON

Some climbers prefer to summit during a full moon. When the peak of Kilimanjaro and magnificent glaciers are lit up by the full moon, the view is absolutely stunning. For this reason alone, some climbers schedule their trek to coincide with this celestial event, occurring once a month. However, a practical reason for climbing at these times is that a bright moon (along with a clear sky) will improve your visibility throughout your climb and most importantly, during the summit attempt.

Below are full moon dates:

| Month | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 12 | 2, 31 | 21 | 10 |

| February | 11 | — | 19 | 9 |

| March | 12 | 2,31 | 21 | 9 |

| April | 11 | 30 | 19 | 8 |

| May | 11 | 29 | 19 | 7 |

| June | 9 | 28 | 17 | 5 |

| July | 9 | 27 | 17 | 5 |

| August | 7 | 26 | 15 | 3 |

| September | 6 | 25 | 14 | 2 |

| October | 5 | 24 | 14 | 31 |

| November | 4 | 23 | 12 | 30 |

| December | 3 | 22 | 12 | 30 |

To summit during a full moon, a 7-day climb should start 5 days prior to the full moon date. It is not necessary to summit on the exact full moon date to take advantage of moonlight. A summit on the day before or the day after is also beneficial. We offer several group climbs with full moon summits every month during the dry season. These dates tend to be the first to book completely full well in advance.

For those who favor a less crowded climb, avoid the full moon completely because these dates attract many climbers.

Another method of dodging crowds is to choose an “off” day of departure. Most climbers will begin their climbs on Saturday, Sunday or Monday, with routes lasting 6 to 7 days. We have many clients who climb with or without the full moon, and clients are equally satisfied with either itinerary. You can go anytime but do it sooner rather than later.

As we have now referenced the unique nature of Kilimanjaro and how and when to climb it, let’s share a little more about its geology. Read on for more information on the natural landscape of the area.

KILIMANJARO GEOLOGY

Kilimanjaro really is a bizarre geological. Rising 4,800m above the East African plains, 270km from the shores of the Indian Ocean and measuring up to 40 km across, it is the tallest freestanding mountain in the world and one formed, shaped, eroded and scarred by the twin forces of fire and ice. It is actually a volcano, or rather three volcanoes, with the two main peaks, Kibo and Mawenzi, the summits of two of those volcanoes.

The story of its creation goes like this:

The Rift Valley

About three-quarters of a million years ago (making Kilimanjaro a veritable youngster in geological terms), molten lava burst through the fractured surface of the Great Rift Valley, a giant fault in the earth’s crust that runs through East Africa. (Actually, Kilimanjaro lies 50 miles from the East African Rift Valley along a splinter running off it, but that need not concern us here).

The huge pressures behind this eruption pushed part of the Earth’s crust skywards, creating the Shira volcano, the oldest of the volcanoes forming the Kilimanjaro massif. Shira eventually ceased erupting around 500,000 years ago, collapsing as it did so to form a huge caldera (the deep cauldron-like cavity on the summit of a volcano) many times the size of its original crater.

The Formation of Kibo and Mawenzi

Soon after Shira’s extinction, Mawenzi started to form following a further eruption within the Shira caldera. Though much eroded, Mawenzi has at least kept some of its volcanic shape to this day. Then, 460,000 years ago, an enormous eruption just west of Mawenzi caused the formation of Kibo. Continual subterranean pressure forced Kibo to erupt several times more, forcing the summit ever higher until reaching a maximum height of about 5900m.

A further huge eruption from Kibo 100,000 years later led to the formation of Kilimanjaro’s characteristic shiny black stone – which in reality is just solidified black lava or obsidian. This spilled over from Kibo’s crater into the Shira caldera and around to the base of the Mawenzi peak, forming the so-called SaTddle. Later eruptions created a series of distinctive mini-cones, or parasitic craters, that run in a chain south-east and north-west across the mountain, as well as the smaller Reusch Crater inside the main Kibo summit.

The last volcanic activity of note was just over 200 years ago. It left a symmetrical inverted cone of ash in the Reusch Crater, known as the Ash Pit, which can still be seen today.

Kilimanjaro’s Glaciers

What makes Mount Kilimanjaro especially unique is that despite its close proximity to the equator, it is crowned with ice. The glaciers have existed here for more than 11,000 years. They used to be more than 300 feet (100 m) deep and extended 6,500 feet (2,000 m) from the mountaintop. However, due to global warming and long-term climatic cycles, the ice has been vaporizing at an alarming rate. Some scientists estimate that Mount Kilimanjaro’s ice cap will be completely gone by 2050. (If you are contemplating the climb, do yourself a favor and do it sooner rather than later. The glaciers are something you do not want to miss!)

Today, Uhuru Peak, the highest part of Kibo’s crater rim and the goal of most trekkers, stands at around 5895m. The fact that the summit is around five metres shorter today than it was 450,000 years ago can be ascribed in part to some improved technology, which has enabled scientists to measure the mountain more accurately; and in part to the simple progress of time and the insidious glacial erosion down the millennia. These glaciers, advancing and retreating across the summit, created a series of concentric rings like terraces near the top of this volcanic massif on the western side.

The Furtwangler Glacier on the Kibo Summit

The Kibo peak has also subsided slightly over time. About one 100,000 years ago, a landslide took away part of the external crater, creating the Kibo Barranco or the Barranco Valley (home to one of the mountain’s more popular campsites).

The glaciers were also behind the formation of the valleys and canyons, eroding and smoothing the earth into gentle undulations all around the mountain. This happened less so on the northern side, where the glaciers, on the whole, failed to reach. This left the valleys sharper and more defined.

Is Kilimanjaro Now an Extinct Volcano?

While eruptions are unheard of in recent times, Kibo is classified as being dormant rather than extinct, as anybody who visits the inner Reusch Crater can testify:

- A strong sulphur smell still rises from the crater.

- The earth is hot to touch, preventing ice from forming.

- Occasionally fumaroles escape from the Ash Pit that lies at its heart.

WHAT DOES KILIMANJARO LOOK LIKE?

So, you’ve heard there are glaciers. You know it is a volcano. But what does Kilimanjaro look like? Kilimanjaro is not only the highest mountain in Africa, it’s also one of the biggest volcanoes on Earth, covering an area of approximately 388,500 hectares.

THE SUMMITS OF KILIMANJARO

Within this 388,500-hectare area, there are three main peaks.

The Kibo Summit

The Kibo summit is the best preserved crater on the mountain; its southern lip is slightly higher than the rest of the rim, and the highest point on this southern lip is known as Uhuru Peak. At 5895 m, this is highest point in Africa and the goal of just about every Kilimanjaro trekker. Kibo is also the only one of the three summits which is permanently covered in snow, thanks to the large glaciers that cover large – though diminishing – areas of its surface.

Kibo Summit

Kibo is also the one peak that really does look like a volcanic crater; indeed, there are three concentric craters on Kibo

Reusch Crater & Ash Pit

Within the inner Reusch Crater (1.3 km in diameter) one can still see signs of volcanic activity, including fumaroles, the smell of sulphur and a third crater – the Ash Pit, which is 130m deep by 140m wide.

The outer, Kibo Crater (1.9 by 2.7km), is not a perfect, unbroken ring. There are gaps in the summit where the walls have been breached by lava flows; the most dramatic of these is the Western Breach.

Kibo’s Western Breach

Perhaps the most important feature of Kibo, however, is that its slopes are gentle. This feature means, of course, that trekkers and more experienced mountaineers are able to reach the summit.

Mawenzi

Mawenzi is the second highest peak on Kilimanjaro. Seen from Kibo, Mawenzi looks less like a crater than a single lump of jagged, craggy rock emerging from the Saddle (see ‘Other features of Kilimanjaro’ below). This is because its western side also happens to be its highest, hiding everything behind it.

Walk around Mawenzi, however, and you’ll realize that this peak is actually a horseshoe shape, with only the northern side of the crater eroded away. Its sides are too steep to hold glacier. Also, there is no permanent snow on Mawenzi, and the gradients are enough to dissuade all but the bravest and most technically accomplished climbers.

Mawenzi’s highest point is Hans Meyer Peak at 5149 m. However, this summit is so shattered and riven with gullies and fractures. There are a number of other distinctive peaks including Purtscheller Peak (5120m) and South Peak (4958 m). There are also two deep gorges, the Great Barranco and the Lesser Barranco, scarring its north-eastern face.

The Shira Ridge

The oldest and smallest summit on Kilimanjaro is known as the Shira Ridge, which lies on the western edge of the mountain. This is the least impressive peak, being nothing more than a heavily eroded ridge. Its highest point, Johnsell Point, is 3962 m tall. This ridge is, in fact, merely the western and southern rims of the crater formed by the original volcanic eruption.

OTHER FEATURES OF KILIMANJARO

Separating Kibo from the second peak, Mawenzi, is the Saddle. At 3600 ha, it is the largest area of high altitude tundra in tropical Africa. This really is a beautiful, eerie place: a dusty desert almost 5000m high, featureless except for the occasional parasitic cone dotted here and there, including the Triplets, Middle Red and West Lava Hill. These all run south-east from the south-eastern side of Kibo.

These are just some of the 250 parasitic cones that are said to stand on Kilimanjaro. Few people know this, but Kilimanjaro does actually have a crater lake. Lake Chala (aka Jala) lies some 30km to the south-east and is said to be up to 2.5 miles deep.

The Shira Plateau is a large, rocky plateau, 6200 ha in size, that lies to the west of the Kibo summit (between Kibo and the Shira Ridge). It is believed to be the caldera of the first volcanic eruption (a caldera is a collapsed crater) that has been filled in by lava from later eruptions, which then solidified and turned to rock.

Look down at Kilimanjaro from above and you should be able to count seven paths trailing like ribbons up the sides of the mountain. Five of these are ascent-only paths (ie you can only walk up the mountain on them and are not allowed to come down on these trails); one, Mweka, is a descent-only path, and one – the Marangu Route – is both an ascent and descent trail.

At around 4000 m, these trails meet up with a path that loops right around the Kibo summit. This path is known as the Kibo Circuit, though it’s often divided into two halves, known as the Northern and Southern circuits. From here, three further paths lead up the slopes to the summit itself.

KILIMANJARO GLACIERS

At first sight, Kilimanjaro’s glaciers look like nothing more than big smooth piles of slightly monotonous ice. On second sight, they pretty much look like this too. However, there’s much more to Kili’s glaciers than meets the eye. These cathedrals of gleaming, blue-white ice are dynamic repositories of climatic history – and they could also be providing us with a portent for impending natural disaster.

You would think that with the intensely strong equatorial sun, glaciers wouldn’t exist at all on Kilimanjaro. In fact, it is the brilliant white colour of the ice that allows it to survive as it reflects most of the heat. The dull black lava rock on which the glacier rests, on the other hand, does absorb the heat; so while the glacier’s surface is unaffected by the sun’s rays, the heat generated by the sun-baked rocks underneath leads to glacial melting.

As a result, the glaciers on Kilimanjaro are inherently unstable:

- The ice at the bottom of the glacier touching the rocks melts.

- The glaciers lose their ‘grip’ on the mountain and ‘overhangs’ occur where the ice at the base has melted away, leaving just the ice at the top to survive.

- As the process continues, the ice fractures and breaks away, exposing more of the rock to the sun…

- And so the process begins again.

The sun’s effect on the glaciers is also responsible for the spectacular structures – the ice columns and pillars, towers and cathedrals – that are the most fascinating part of the upper slopes of Kibo.

Why Haven’t Kilimanjaro’s Glaciers Melted Away?

According to recent research, the current glaciers began to form in 9,700 BC. One would have thought that, after 11,700 years of this melting process, very little ice would remain on Kilimanjaro. The fact that there are still glaciers is due to the prolonged ‘cold snaps’, or ice ages, that have occurred down the centuries. These have allowed the glaciers to regroup and reappear on the mountain.

According to estimates, there have been at least eight of these ice ages; the last a rather minor one in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, a time when the Thames frequently froze over and winters were severe. At these times, the ice on Kilimanjaro would have reached right down to the tree line in places and both Mawenzi and Kibo would have been covered.

At the other extreme, before 9,700 BC, there have been periods when Kilimanjaro was completely free of ice, perhaps for up to 20,000 years.

KILIMANJARO FLORA

It is said that to climb up Kilimanjaro is to walk through four seasons in four days.

It is true, of course, and nowhere is this phenomenon more apparent than in its flora. The variety of flora found on Kilimanjaro can be ascribed in part to the mountain’s tremendous height and, in part, to its proximity to both the equator and the Indian Ocean. Also add the variations in climate, solar radiation, and temperature from the top of the mountain to the bottom, and you end up with the ideal conditions for highly differentiated and distinctive vegetation zones.

Cultivated Zone and Forest (800 m – 2,800 m)

The forest zone, along with the cultivated zone that lies below it, receives the most rainfall – about 2300mm per year – of any part of the mountain. The forest zone also houses the greatest variety of both fauna and flora.

The star of the montane forest zone is the beautiful flower Impatiens kilimanjari, an endemic fleck of dazzling red and yellow in the shape of an inch-long tuba. You’ll see them by the side of the path on the southern side of the mountain. Vying for the prime piece of real estate, the area between the roots of the trees, are equally elegant flowers. These include the beautiful violet Viola eminii and Impatiens pseudoviola.

Heath and Moorland (2, 800 m – 4,000 m)

These two zones overlap. Together, they occupy the area immediately above the forest from about 2,800 m to 4,000 m – known as the low alpine zone. Temperatures can drop below 0°C here; most of the precipitation that does fall here comes from the mist that is an almost permanent fixture at this height.

Immediately above the forest zone is the alpine heath. Rainfall here is around 1,300 mm per year. Grasses now dominate the mountain slopes, picked out here and there with some splendid wild flowers that include the yellow-flowered Protea kilimandscharica. Another favorite, and one most readers will recognise instantly, is the back-garden favorite: Kniphofia thomsonii, better known to most as the red-hot poker.

Climbing even further, you’ll soon reach the imperceptible boundary of the moorland zone, which tends to have clearer skies but an even cooler climate. Average per annum precipitation is now down to 525mm. The most distinctive plant in this area – indeed, on the entire mountain – is the senecio, or giant or tree groundsel (below right). Groundsels tend to favour the damper, more sheltered parts of the mountain, which is why you’ll see them in abundance near the Barranco Campsite as well as other, smaller valleys and ravines.

Sharing roughly the same kind of environment is the strange lobelia deckenii (left), another endemic species and one that bears no resemblance to the lobelias that you’ll find in your back garden.

Alpine Desert (4,000 m – 5,000 m)

By the time you reach the Saddle, only three species of tussock grass and a few everlastings can withstand the extreme conditions. This is the Alpine Desert, where plants have to survive in drought conditions (precipitation here is less than 200mm per year) and put up with both inordinate cold and intense sun – usually in the same day.

Up to about 4,700 m, you’ll also find the Asteraceae, a bright yellow daisy-like flower and the most cheerful-looking organism at this height.

On Kibo, almost nothing lives. There is virtually no water. On the rare occasions that precipitation occurs, most of the moisture instantly disappears into the porous rock or is locked away in the glaciers.

That said, specimens of Helichrysum newii – an everlasting that truly deserves that name – have been found near a fumarole in the Reusch Crater. This is a good 5,760 m above sea level.

Lichen is said to exist right up to the summit. While these lichens may not be the most spectacular of plants, their growth rate on the upper reaches of Kilimanjaro is estimated to be just 0.5 mm in diameter per year; for this reason, scientists have concluded that the larger lichens on Kilimanjaro could be amongst the oldest living things on earth, being hundreds and possibly thousands of years old!

WILDLIFE ON KILIMANJARO

Most animals prefer to be somewhere where there aren’t 35,000 people marching around every year! So in all probability, you will see virtually nothing during your time on the mountain beyond the occasional monkey or mouse.

Nevertheless, keep your eyes open and you never know…

Forest and Cultivated Zones

Animals are most numerous in the forest zone; unfortunately, so is the cover provided by trees and bushes; this means sightings remain rare.

As with the four-striped grass mice of Horombo, there are only a few species for whom the arrival of man has been a boon rather than a curse, including the blue monkeys, which appear daily near the Mandara Huts and which are not actually blue; they are typically grey or black with a white throat.

These are the plainer relatives of the beautiful colobus monkey, which has the most enviable tail in the animal kingdom; you can see a troop of these at the start of the forest zone on the Rongai Route, by Londorossi Gate and a few near the Mandara Huts too.

Olive baboons, civets, leopards, mongooses and servals are said to live in the mountain’s forest as well, though sightings are extremely rare; here, too, lives the bush pig – with a distinctive white stripe running along its back from head to tail.

Then, there’s the honey badger. Don’t be fooled by the rather cute name. As well as being blessed with a face only its mother could love, these are the most powerful and fearless carnivores for their size in Africa. Even lions give the honey badger a wide berth. You should, too: not only can they cause damage, but the thought of having to tell your friends that, of all the bloodthirsty creatures that roam the African plains, you got savaged by a badger…Well, it is too shaming to contemplate!

Of a similar size, the aardvark has enormous claws but, unlike the honey badger, this nocturnal, long-snouted anteater is entirely benign. So, fear not: As the old adage goes, an aardvark never killed anyone. Both aardvarks and honey badgers are rarely, if ever, seen on the mountain. Nor are porcupines, Africa’s largest rodents. Though also present in this zone, they are both shy and nocturnal and your best chances of seeing one is as roadkill on the way to Dar es Salaam.

Further down, near or just above the cultivated zone, bushbabies are more easily heard than seen as they come out at night and jump on the roofs of the huts. Here, too, is the small-spotted genet, with its distinctive black-and-white tail, and the noisy, chipmunk-like tree hyrax.

One creature you definitely won’t see at any altitude is the rhinoceros. Although a black rhinoceros was seen a few years ago on the north side of the mountain, it is now believed that over-hunting has finally taken its toll of this most majestic of creatures; Count Teleki is said to have shot 89 of them during his time in East Africa, including four in one day, and there are none on – or anywhere – near Kilimanjaro today.

Heath, Moorland and Above

Just as plant-life struggles to survive much above 2,800 m, animals also find it difficult to live on the barren upper slopes. Yet though we may see little, there are a few creatures living on Kilimanjaro’s higher reaches.

Above the treeline, you’ll be lucky to see much. The one obvious exception to this rule is the four-striped grass mouse, which clearly doesn’t find it a problem eking (or should that be eeking?) out an existence at high altitude.

Indeed, if you’re staying in the Horombo Huts on the Marangu Route, one is probably running under your table. And if you stand outside for more than a few seconds at any campsite, you should see them scurrying from rock to rock. Other rodents present at this level include the harsh-furred and climbing mouse and the mole rat, though all are far more difficult to spot.

For anything bigger than a mouse, your best chance above 2800m is either on the Shira Plateau, where lions are said to roam occasionally or on the northern side of the mountain on the Rongai Route. Kenya’s Amboseli National Park lies at the foot of the mountain on this side and many animals, particularly elephants, amble up the slopes from time to time.

Grey and red duikers, elands and bushbucks are perhaps the most commonly seen animals at this altitude, though sightings are still extremely rare. None of these larger creatures live above the tree-line of Kilimanjaro permanently, however. As with the leopards, giraffes, and buffaloes that occasionally make their way up the slopes, they are like us – no more than day-trippers.

On Kibo itself, the entomologist George Salt found a species of spider that was living in the alpine zone at altitudes of up to 5,500 m. What exactly these high-altitude arachnids live on up there is unknown – though Salt himself reckoned it was probably the flies that blew in on the wind, of which he found a few, and which appeared to be unwilling or unable to fly. What is known is that the spiders live underground, better to escape the rigours of the weather.

Avifauna

Kilimanjaro is great for birdlife:

- The cultivated fields on the lower slopes provide plenty of food.

- The forest zone provides shelter and is ideal for nesting sites.

- The barren upper slopes are ideal hunting grounds for raptors.

In the forest, look out for the noisy dark green Hartlaub’s turaco. It’s easy to distinguish when it flies because of its bright red under-wings. The silvery-cheeked hornbills and speckled mousebirds hang around the fruit trees in the forest, particularly the fig trees. There’s also the trogon which, despite a red belly, is difficult to see because it remains motionless in the branches. Smaller birds include the Ruppell’s robin chat (black and white head, grey top, orange lower half) and the common bulbul, with a black crest and yellow beneath the tail.

Further up the slopes, the noisy, scavenging, garrulous white-necked raven is a constant presence on the heath and moorland zones. It’s eternally hovering on the breeze around the huts and lunch stops, on the lookout for any scraps. Smaller, but just as ubiquitous, is the alpine chat, which is a small brown bird with white side feathers in its tail, and the streaky seedeater, another brown bird (with streaks on its back) that often hangs around the huts. The Alpine swift also enjoys these misty, cold conditions.

The prize for the most beautiful bird on the mountain, however, goes to the dazzling scarlet-tufted malachite sunbird. Metallic green, save for a small scarlet patch on either side of its chest, this delightful bird can often be seen hovering above the grass, hooking its long beak into reach the nectar from the giant lobelias or feeding on the lobelias.

Climbing further, we come to raptor territory. You’ll rarely see these birds up close, as they spend most of the day gliding on the currents looking for prey. The mountain and augur buzzards are regularly spotted hovering above the Saddle (a specimen of the former also hangs about the School Huts when it’s quiet).

These are impressive birds in themselves – especially if you’re lucky enough to see one up close. Although neither is as large as the enormous crowned eagle or the rare Lammergeyer, a giant vulture with long wings and a wedge tail.

As the elevation rises, the scenery and wildlife changes. But so does the altitude.

WHAT ABOUT ACUTE MOUNTAIN SICKNESS (AMS)?

From the animals to the plant life, there is so much beauty to take in on the Kilimanjaro trek. However, there is also less oxygen. The percentage of oxygen in the atmosphere at sea level is about 21%. As altitude increases, the percentage remains the same but the number of oxygen molecules per breath is reduced. At 12,000 feet (3,600 meters) there are roughly 40% fewer oxygen molecules per breath. This means the body must adjust to having less oxygen.

Altitude sickness, known as AMS, is caused by the failure of the body to adapt quickly enough to the reduced oxygen at increased altitudes. Altitude sickness can occur in some people as low as 8,000 feet (2,440 meters), but serious symptoms do not usually occur until over 12,000 feet (3,650 meters).

At over 10,000 feet (3,000 meters), more than 75% of climbers will experience at least some form of mild AMS.

Important to note: Our guides are all experienced in identifying altitude sickness and dealing with the problems it causes with climbers. They will constantly monitor your well-being on the climb by watching you and speaking with you.

That being said, mountain medicine recognizes three altitude categories:

- High altitude: 4,900 to 11,500 ft (1,500 to 3,500 m)

- Here, AMS and decreased performance is common.

- Very high altitude: 11,500 to 18,000 ft (3,500 to 5,500 m)

- Here, AMS and decreased performance are expected.

- Extreme altitude: 18,000 ft and above (5,500 m and above)

- In extreme altitude, humans can function only for short periods of time, with acclimatization.

Mount Kilimanjaro’s summit stands at 19,340 feet (5,895 meters) – in extreme altitude.

There are four factors that contribute to experiencing AMS:

- High Altitude

- Fast Rate of Ascent

- High Degree of Exertion

- Dehydration

The main cause of altitude sickness is going too high (in altitude) at too fast a pace (rate of ascent).

But, given enough time, your body will adapt to the decrease in oxygen at a specific altitude. This process is known as acclimatization and generally takes one to three days at any given altitude.

Several changes take place in the body that enable it to cope with decreased oxygen:

- The depth of respiration increases.

- The body produces more red blood cells to carry oxygen.

- Pressure in pulmonary capillaries is increased, “forcing” blood into parts of the lung which are not normally used when breathing at sea level.

- The body produces more of a particular enzyme that causes the release of oxygen from hemoglobin to the body tissues.

Again, AMS is very common at high altitude. It is difficult to determine who may be affected by altitude sickness since there are no specific factors such as age, sex, or physical condition that correlate with susceptibility.

WHEN AND WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS OF ALTITUDE SICKNESS?

The symptoms of AMS usually start 12 to 24 hours after arrival at altitude. They normally disappear within 48 hours. The symptoms of Mild AMS include:

- Headache

- Nausea & Dizziness

- Loss of appetite

- Fatigue

- Shortness of breath

- Disturbed sleep

- General feeling of malaise

Symptoms tend to be worse at night and when respiratory drive is decreased. Mild AMS does not interfere with normal activity and symptoms generally subside as the body acclimatizes. As long as symptoms are mild, and only a nuisance, ascent can continue at a moderate rate.

While hiking, it is essential that you communicate any symptoms of illness immediately to others on your trip.

The signs and symptoms of Moderate AMS include:

- Severe headache that is not relieved by medication

- Nausea and vomiting, increasing weakness and fatigue

- Shortness of breath

- Decreased coordination (ataxia)

Normal activity is difficult at this level, although the person may still be able to walk on their own. At this stage, only advanced medications or descent can reverse the problem. It is important to get the person to descend before the ataxia reaches the point where they cannot walk on their own (which would necessitate a stretcher evacuation).

Descending only 1,000 feet (300 meters) will result in some improvement, and 24 hours at the lower altitude will result in a significant improvement. The person should remain at lower altitude until all the symptoms have subsided. At this point, the person has become acclimatized to that altitude and can begin ascending again.

Continuing on to higher altitude while experiencing moderate AMS can lead to death. This may sound scary, but as long as you stay mindful and keep your group and guides informed, you can take the proper steps and precautions.

Severe AMS results in more severe versions of the aforementioned symptoms, including:

- Shortness of breath at rest

- Inability to walk

- Decreasing mental status

- Fluid build-up in the lungs

Severe AMS requires immediate descent of around 2,000 feet (600 meters) to a lower altitude.

There are two serious conditions associated with severe altitude sickness:

- High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE)

- High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE).

Both of these happen less frequently, especially to those who are properly acclimatized. But, when they do occur, it is usually in people going too high too fast or going very high and staying there. In both cases, the lack of oxygen results in leakage of fluid through the capillary walls into either the lungs or the brain.

Again, this may sound scary – but keeping your guides and group informed, as well as being candid about any symptoms you’re experiencing – can help prevent these. It’s good to be aware though; read on to get more details.

High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE)

HAPE results from fluid build up in the lungs. This fluid prevents effective oxygen exchange. As the condition becomes more severe, the level of oxygen in the bloodstream decreases, which leads to cyanosis, impaired cerebral function and, eventually, death.

Symptoms of HAPE include:

- Shortness of breath at rest

- Tightness in the chest

- Persistent cough bringing up white, watery, or frothy fluid

- Marked fatigue and weakness

- A feeling of impending suffocation at night

- Confusion, and irrational behavior

Confusion, and irrational behavior are signs that insufficient oxygen is reaching the brain. In cases of HAPE, immediate descent of around 2,000 feet (600 meters) is a necessary life-saving measure. Anyone suffering from HAPE must be evacuated to a medical facility for proper follow-up treatment.

High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE)

HACE is the result of the swelling of brain tissue from fluid leakage. Symptoms of HACE include:

- Headache

- Weakness

- Disorientation

- Loss of coordination

- Decreasing levels of consciousness

- Loss of memory

- Hallucinations and Psychotic behavior

- Coma

This condition is rapidly fatal unless the afflicted person experiences immediate descent. Anyone suffering from HACE must be evacuated to a medical facility for follow-up treatment.

PROPER ACCLIMATIZATION GUIDELINES

Luckily, the right steps can help you climb the mountain safely.

To acclimatize, this is what we recommend:

- Pre-acclimatize prior to your trip by using a high altitude training system.

- Ascend Slowly. Your guides will tell you, “Pole, pole” (slowly, slowly) throughout your climb. Because it takes time to acclimatize, your ascension should be slow. Taking rest days will help. Taking a day to rest increases your chances of getting to the top by up to 30%. It also increases your chances of getting enjoyment out of the experience by much more than that!

- Do not overexert yourself. Mild exercise may help altitude acclimatization but strenuous activity may promote HAPE.

- Take slow deliberate deep breaths.

- Climb high, sleep low. Climb to a higher altitude during the day, then sleep at a lower altitude at night. Most routes comply with this principle and additional acclimatization hikes can be incorporated into your itinerary.

- Eat enough food and drink enough water while on your climb. It is recommended that you drink from four to five liters of fluid per day. Also, eat a high-calorie diet while at altitude, even if your appetite is diminished.

- Avoid tobacco, alcohol and other depressant drugs including, barbiturates, tranquilizers, sleeping pills, and opiates. These further decrease the respiratory drive during sleep resulting in a worsening of altitude sickness.

- If you begin to show symptoms of moderate altitude sickness, don’t go higher until symptoms decrease. If symptoms increase, descend.

Remember, our guides are highly experienced in identifying altitude sickness and dealing its symptoms. They will constantly be there to monitor your well-being on the climb – watching you and speaking with you to see how you’re feeling.

It is important that you be open, active and honest with your guide. If you do not feel well, do not try to pretend you are fine. Do not mask your symptoms and say you feel OK. Only with accurate information can your guide best treat you.

We do want to share this: To put your safety first, there is always the chance that you will have to abandon your climb. In these situations, the guide will have you to descend. This is an order that is for your own safety. The guide’s decision is final.

Please, do not try to convince your guide to change the decision (whether with words, threats or money!) to continue your climb. They really do have you and your safety top of mind. The guide wants you to succeed on your climb but will not jeopardize your health. In short, please do respect the decision of the guide.

BOTTLED OXYGEN

We are all about precautions and safety.

This is why we carry bottled oxygen on all of our climbs; it is a precaution and additional safety measure. The oxygen canister is for use only in emergency situations. It is NOT used to assist clients who have not adequately acclimatized on their own to climb higher. The most immediate treatment for moderate and serious altitude sickness is descent. With Kilimanjaro’s routes, it is always possible to descend and descend quickly. Therefore, oxygen is used strictly to treat a stricken climber, when necessary, in conjunction with descent, to treat those with moderate and severe altitude sickness.

We are aware that some operators market the use of supplementary personal oxygen systems as a means to eliminate the symptoms of AMS. However, to administer oxygen in this manner and for this purpose is dangerous. That is because it is only a temporary treatment of altitude sickness. Upon the cessation of oxygen use, you will be at an even higher altitude without proper acclimatization.

99% of the companies on Kilimanjaro do NOT offer supplementary oxygen – because it is potentially dangerous, wholly unnecessary and against the spirit of climbing Kilimanjaro. The challenge of the mountain lies within the fact that the summit is at a high elevation, where climbers must adapt to lower oxygen levels at altitude.

WHAT IF YOU DID NEED A PORTABLE STRETCHER?

Large, one-wheeled rescue stretchers are found on Mount Kilimanjaro, but they are only available within a small area of the park. This means that getting a climber down the mountain could pose difficult challenges for Kilimanjaro operators.

Luckily, at Jambo Kilimanjaro, we carry a portable stretcher at all times in case of emergencies, such as when a climber is unable to walk on their own and the trekking party is some distance away from the park’s stretchers. Our portable stretchers are compact, strong and lightweight. The device can be used to evacuate an injured climber quickly off the mountain. To use, the subject is secured to the stretcher using straps. Then porters hold on to the hand grips to usher the climber to safety.

It’s as easy as that.

IS THERE MEDICINE TO TREAT AMS? MEET DIAMOX AND IBUPROFEN

Diamox (generic name acetazolamide) is an F.D.A. approved drug for the prevention and treatment of AMS. The medication acidifies the blood, which causes an increase in respiration, thus accelerating acclimatization. Diamox does not disguise symptoms of altitude sickness; it prevents them.

Studies have shown that Diamox results in fewer and/or less severe symptoms of acute mountain sickness (AMS) when

the climber:

- Has a dose of 250 mg.

- Takes it every eight to twelve hours.

- Does this before and during rapid ascent to altitude.

The medicine should be continued until you are below the altitude where symptoms become bothersome. Side effects of acetazolamide include tingling or numbness in the fingers, toes and face, taste alterations, excessive urination; and rarely, blurring of vision. These go away when the medicine is stopped.

It is a personal choice of the climber whether or not to take Diamox as a preventative measure against AMS. (Jambo Kilimanjaro® neither advocates nor discourages the use of Diamox.)

Ibuprofen can be used to relieve altitude-induced headaches, too.

For more questions about health, safety and the general mountain experience, don’t hesitate to ask our team.